By Thomas Ultican 10/8/2025

Horace Mann, frequently referred to as the “father of public education”, declared that public education should be nonsectarian. He was responding to a dispute in the Protestant community between the Congregationalists, Unitarians, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Presbyterians and other Protestant sects who were threatening to separate from the common schools and form their own parochial systems. Mann countered that schools should restrict themselves to commonly shared Protestant values. He believed such values were the principles of civic ethics necessary for participation in our republican form of government. Katherine Stewart reported, “Representatives of a number of sects immediately and vigorously attacked him, but large majorities agreed with this policy, and it soon became the norm in the ‘common school,’ or public school movement.”

As long as the overwhelming majority of Americans were Protestant, this solution was workable. However, the Catholic community was growing. The 25,000 American Catholics in 1790 represented less than 1% of the population. By 1820, their 195,000 members were 2% of American people. In 1830 they were at 318,000 (2.5%), in 1840 663,000 (3.9%) and in 1850 their ranks grew to 1,600,000 (6.9%). (See “Religion in America; A Political History” By Denis Lacorne Page 64) The Catholics were becoming a bigger group with growing influence.

In his book, “Schooled to Order: a Social History of Public Schooling in America” Professor David Nasaw noted that common school textbooks were filled with racist characterization of the Irish and disdain for the Pope. The Catholic clergy were described as “libertine, debauched, corrupt, wicked, immoral, profligate, indolent, slothful, bigoted, parasitic, greedy, illiterate, hypocritical and pagan.” Catholic parents did not want to expose their children to this and they did not like daily readings from the King James Bible instead of their preferred Douai-Rheims Bible.

Before we go on, a little background on these two Bibles. The Douai–Rheims Bible is a translation of the Bible from the Latin Vulgate into English made by members of the English College, Douai, in the service of the Catholic Church. The New Testament portion was published in Reims, France, in 1582, and the Old Testament portion was published twenty-seven years later in 1610 by the University of Douai. The Latin Vulgate is a translation of Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek texts, accomplished in 382 mainly by Saint Jerome.

The King James Bible is an Early Modern English translation sponsored by King James I of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611. The source material for the translation includes the Latin Vulgate plus Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek texts.

Although very similar to each other there are some differences. However, early 19th century bigotry trumped all differences. In her study of 19th century textbooks, Ruth Miller Elson showed that anti-Catholic propaganda was a staple of allegedly disinterested lessons on non-religious topics. In history, they learned “the Roman Catholic religion completed” the Roman Empire’s “degeneracy and ruin.” Lessons in patriotism taught that the founding fathers would never “have bowed to papal infallibility, or paid the tribute to St. Peter.” Evan textbooks that commended tolerance in matters of religion were “full of the horrible deeds of the Catholics.”

Maybe it is not so shocking how violent the Catholic-Protestant dispute became. One of the deadliest episodes in early American history occurred in 1844 when Protestants and Catholics took to the streets of Philadelphia. After two weeks of rioting, twenty-five people laid dead in the streets, more than one-hundred were wounded and dozens of homes as well as two churches were torched.

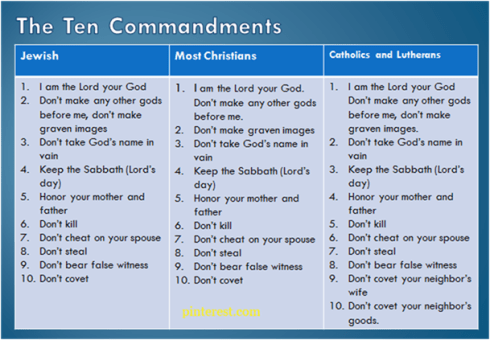

In 1859, a watershed moment occurred in Boston involving a ten-years old student, Thomas Whall. He refused to read the Ten Commandments at the beginning of his morning class at Eliot School, a Boston public school. Young Whall refused based on the fact that these Commandments were from the King James Bible. By this act he was breaking Massachusetts law. The principal “whipped” him on the hands with a rattan stick until his fingers were bleeding and Whall fainted. He would not yield. Whall’s fellow students followed his lead and refused to obey. Hundreds of them were expelled. (Lacorne Page 72)

After Whall’s father sued the principal for using excessive force, Judge Sebeus Maine found for the school and its principal. He said that Thomas’s refusal threatened the stability of the public school, “the granite foundation upon which our republican form of government rests.”He indicated the readings were free of dogma; it was all done objectively with no inappropriate comments. Therefore, there was no violation of freedom of conscience. (Lacorne Page 73)

Katherine Stewart reported:

“This incident led Catholic leaders to conclude that public schools could not serve their community. In response, they launched a movement to create Catholic parochial schools in Boston and across the nation.”

No Compromise

The disdain and prejudice against Catholics was deeply ingrained in Ohio. University of Cincinnati’s former writing coach, Deborah Rieselman quotes associate history professor Linda Przybyszewski:

‘“It was very respectable then to be anti-Catholic,’ notes Przybyszewski. ‘Neighborhoods were often segregated. In 1844, after Cincinnati newspapers carried stories of anti-Catholic riots on the east coast, a group of men threw sticks and rocks at a house occupied by Catholic clergy, according to a German priest who had immigrated to Cincinnati.”’

“Even the Rev. Lyman Beecher, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s father, was a vocal opponent of Catholics. Considered a progressive thinker because he was a black abolitionist and the founder of a Cincinnati seminary, Beecher preached a ‘papal conspiracy theory’ that Catholics would take over the West.”

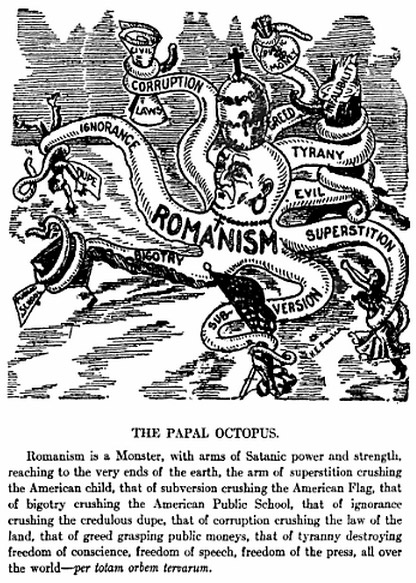

An Anti-Catholic Cartoon

In 1869, a fierce political and legal battle erupted in Cincinnati, Ohio. For some time there had been discussions on the school board about the possibility of uniting the public schools and the Catholic system. There were more than 12,000 students in the Catholic parochial system. One of the keys to the new plan was that there would be no Bible reading in classes.

Ohio State History Teacher, Harold M. Helfman, wrote:

“The bitter clash between those maintaining pro-Bible and anti-Bible viewpoints was to drive both groups into positions of no surrender; their mutually hostile attitudes were to be seized upon by societies, editors, lecturers, ministers, and politicians bent on stirring up latent anti-Popery passions. The board of education’s action was destined to be the focus of a public opinion which plunged Cincinnati into a boiling caldron of fear and bigotry.”

Top legal minds in Ohio fought this battle out in the courts with the Ohio Supreme Court ruling in favor of the Board of Education and their no Bible reading plan. In a subsequent election, most of the board members who voted for the plan were reelected. Unfortunately, the attempts to unify the schools systems were ended by the associated vitriol.

The anti-Catholic bias in America was deeply held by many Protestants; lasting a long time. During the Presidential election campaign of 1960 between Kennedy and Nixon, former President Harry Truman was asked about the influence of the Pope on Kennedy. He cracked, “It’s not the Pope I’m afraid of, it’s the Pop.” Kennedy became the first Catholic ever elected President of the United States.

As late as 1887, the school day still contained “sacred song,” “the literature of Christendom” and “faithful and fearless Christian teachers,” according to a speech that Cincinnati superintendent E.E. White gave to the National Education Association that year. In 1957, my second grade teacher in King Hill, Idaho read a verse to us from the King James Bible every day.

During his second term, US Grant called on states to prohibit “the teaching in said schools of religious, atheistic, or pagan tenets” and ban “the granting of any school funds or school taxes . . . for the benefit or in aid, directly or indirectly, of any religious sect or denomination.” Grant concluded, “No sectarian tenets shall ever be taught in any school supported in whole or in part by the State, nation, or by the proceeds of any tax levied upon any community.”

James Blaine, a former Republican House Speaker with his own 1876 presidential ambitions, jumped at the political opportunity. He introduced a constitutional amendment seeking to codify Grant’s proposals. Although some argue that these provisions reflect a long and admirable history of separation of church and state advanced by the founders, others maintain that these provisions reflect hate and anti-Catholic bigotry that peaked in the 1870s with the national proposal.

Blaine’s amendment failed in the Senate but has been adopted into the constitution of 37 states. In 2020, the Supreme Court discussed the Blaine amendments in Espinoza vs. Montana. In their decision they the court described the Blaine amendments as being “born of bigotry.” This decision has significantly undermined prohibitions of tax dollars going to religious schools.

Thoughts on Protecting Schools and Children

There is little doubt that running multiple tax supported education systems is less efficient and more expensive. However, if that is what people want; it is doable. Unfortunately, many voucher schools and charter schools are not being held accountable. If we are to have these multiple systems, they must all adhere to public education standards and accountability. That means no discrimination and no turning away undesirable students. No anti-LGBTQ rules, no religious tests and no student academic qualifications when accepting tax payer money.

Recent Comments