By Thomas Ultican 1/28/2024

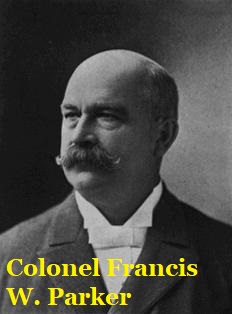

John Dewey called Colonel Francis Wayland Parker, “more than any other person… the father of the progressive education movement.” True, his 1902 passing predated the movement’s heyday by two decades but he was the root, a Civil War veteran and educator, passionate in his quest for better education.

Born (1837) in Bedford, New Hampshire, Colonel Parker was a product of public school. He began his career as a village teacher at 16 and eventually took charge of all grammar schools in his hometown, Piscataquis. Then at 21, he became the principal of a school in Carrolton, Illinois.

During the Civil War, he joined the Union Army as a private in 1861, was elected 1st Lieutenant and later made company commander with the rank of Captain. After being wounded at the Battle of Deep Bottom, Virginia in 1864 and the attack on Fort Fisher, North Carolina, he became commander of the 4th New Hampshire and was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. From then on, he was referred to as Colonel Parker. He was captured, held prisoner in North Carolina in May 1865 and fortunately, the war ended.

After mustering out of the army, Colonel Parker resumed teaching and became head of the normal school in Dayton, Ohio. When an aunt died and bequeathed him $5,000, he traveled to Germany for pedagogy studies.

Progressive Education

Pedagogy practiced in nineteenth century was teacher-centered with extreme discipline. Students were given texts to memorize and lots of drill.

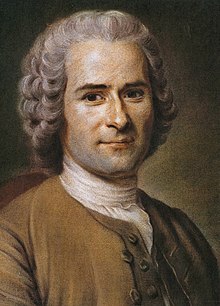

In 1872, Colonel Parker enrolled at Humboldt University of Berlin. He examined new methods of pedagogy developed by European theorists, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Friedrich Froebel, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and particularly Johann Friedrich Herbart.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778) considered his book, Emile or On Education, to be his greatest work, regarded by some as the first philosophy of education in Western culture with a serious claim to completeness. After the French Revolution, Emile served as the inspiration for what became France’s new national system of education. In the book, Rousseau played tutor to Emile and eventually, Sophie. It was here where his philosophy of education came to light. He gives advice like, “Always speak correctly before them, arrange that they enjoy themselves with no one as much as with you, and be sure that … their language will be purified on the model of yours without your ever having chided them.” (Emile Page 71)

Of course, no matter how advanced an 18th century man may be, his ideas can always use some perfecting. In discussing how women should be educated, Rousseau wrote:

“The first education of men depends on the care of women. Men’s morals, their tastes, their pleasures, their very happiness also depend on women. Thus the whole education of women ought to relate to men. To please men, to be useful to them, to make herself loved and honored by them, to raise them when young, to care for them when grown, to counsel them, to console them, to make their lives agreeable and sweet – these are the duties of women at all times, and they ought to be from childhood.” (Emile Page 365)

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi fell in with radical philosophers who supported Rousseau in the mid-18th century. After Emile and Social Contract were published, Rousseau was condemned as a danger to Christianity and state. Pestalozzi’s group wanted freedom and at 19, he wrote many articles, got arrested, charged with helping a newspaper editor escape but was released after three days.

He decided to become an educator, especially of the poor. The Swiss Government put him in charge of an orphanage in Stanz. Here he realized the significance of a universal method of education and spent the rest of his life perfecting one.

German philosopher and educator, Johann Friedrich Herbart, spent a year studying with Pestalozzi. Herbart suggested Pestalozzi read the French book, The Application of Psychology to the Science of Education. Pestalozzi’s French was not great but what he comprehended threw “a flood of light upon my whole endeavor.” (Green, The Educational Ideas of Pestalozzi 48)

In 1805, King Christian the VII of Denmark gifted Pestalozzi a sum of money while he was starting a school at Yverdon. With this, Pestalozzi was able to spend several months writing Views and Experiences relating to the idea of Elementary Education.

Pestalozzi’s method was used by the cantonal school in Aarau that Albert Einstein attended. Einstein said of Aarau, “It made me clearly realize how much superior an education based on free action and personal responsibility is to one relying on outward authority.” (Isaacson, Einstein His Life and Universe 65)

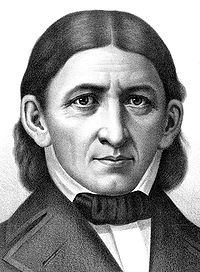

Friedrich Wilhelm August Froebel (1782 – 1852) was the student of Johann Pestalozzi who laid a foundation for modern education, based on recognizing children’s unique needs and capabilities. He created the concept and coined the word kindergarten, which soon entered the English language.

Froebel’s insight recognized the importance of activity for a child’s learning, that games were integral to it and had educational worth. In his book, The Education of Man, he wrote, “A universal and comprehensive plan of human education must, therefore, necessarily consider at an early period singing, drawing, painting, and modeling; it will not leave them to an arbitrary, frivolous whimsicalness but treat them as serious objects for the school.” (Page 228)

Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776 – 1841) was a German philosopher, psychologist and founder of pedagogy as an academic discipline. Homeschooled by his mother until age 12, he studied at the Gymnasium for six years, particularly drawn to philosophy, logic and Kant’s work involving the nature of knowledge.

Stanford’s Encyclopedia of Philosophy says:

“Johann Friedrich Herbart … is known today mainly as a founding figure of modern psychology and educational theory. But these were only parts of a much grander philosophical project, and it was as a philosopher of the first rank that his contemporaries saw him. … In psychology and pedagogy, however, his influence was greater and longer lasting. While no one took over his philosophy or psychology (and especially the impenetrable mathematics) as a whole, certain aspects of his thought proved immensely fruitful. Indeed, without Herbart, the landscape of modern psychology and philosophy would be unrecognizable.”

For the educator, his 1841 book, Outlines of Educational Doctrine, is particularly important and was of great interest to Colonel Parker. In it, Herbart sometimes made concise statements, such as, “A method of study that issues in mere reproduction leaves children largely in a passive state, for it crowds out for the time being the thoughts they would have otherwise had.” (Page 61)In other places, he went into great detail about concepts like preparation, presentation, association, systemization and application.

Returning to America

After Colonel Parker returned to the United States, he noted:

“There was a great deal better way of teaching than anything I had done. Of course I had a great deal of enthusiasm and a great desire to work out the plan and see what I could do.”

He almost immediately secured a position as superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts. Colonel Parker’s innovations, labeled the “Quincy Plan,” gave him a national reputation.

“Quincy Plan” was an experimental program, abandoning prescribed curricula of rote memorization and harsh discipline, replaced with meaningful learning and active understanding. However it had many detractors. In 1879, Quincy students participated in state examinations of traditional subjects. Test results revealed they surpassed all the other students in Massachusetts.

Parker surprisingly responded, “If you ask me to name the best of all in results, I should say, the more human treatment of little folks.”

The following three years, Colonel Parker served as superintendent of Boston public schools. Because of constant opposition to his methods, he left Massachusetts in 1883 to become principal of Cook County Normal School in Chicago, an institute dedicated to training elementary school teachers. Chicago brought strong support from many local luminaries such as Jane Addams, Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch, and Anita McCormack Blaine.

In 1899, to free Parker from the continual harassment by politicians and the school board, Anita McCormack Blaine endowed a private school for him and his faculty. The new Chicago Institute was planned, developed and classes started. It was soon proposed that the Chicago Institute join with the Department of Education to form the School of Education at the University of Chicago. This plan became official on July 1, 1901 with Colonel Parker as director for the School of Education and John Dewey remaining Head Professor in the Graduate School of Arts, Literature and Science. In March 1902, Parker died and John Dewey was appointed his successor in the School of Education.

Anita McCormack Blaine also convinced Colonel Parker to establish the Francis W. Parker School, a private school, in Chicago’s Lincoln Park. This school, established in 1899, was to operate according to Parker’s education principles. A second Francis W. Parker School was founded in San Diego in 1912 with a city population of only 39,000.

Both private schools are still operating and very successful today.

Recent Comments