By Thomas Ultican 6/15/2024

At the dawn of the 19th century, a need to educate the masses was becoming more apparent. Political leaders, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, called for taxpayer-supported public education. However, real or important education was for boys only. There was some movement to educate girls but it was mostly directed toward domestic utility and female etiquette; not the more rigorous boys’ curriculum.

Jean Jacques Rousseau’s famous book, Emile, captured the attitude:

“The good constitution of children initially depends on that of their mothers. The first education of men depends on the care of women. Men’s morals, their passions, their tastes, their pleasures, their very happiness also depend on women. Thus the whole education of women ought to relate to men. To please men, to be useful to them, to make herself loved and honored by them, to raise them when young, to care for them when grown, to counsel them, to console them, to make their lives agreeable and sweet – these are the duties of women at all times, and they ought to be taught from childhood. So long as one does not return to this principle, one will deviate from the goal, and all the precepts taught to women will be of no use for their happiness or for ours.” (Page 365)

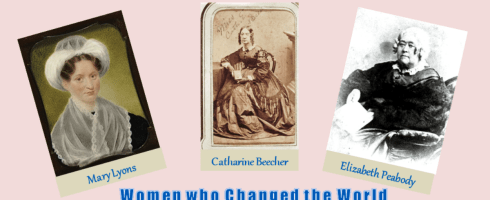

In this environment bereft of encouragement, several amazing women stood up and changed the world. They struggled to educate themselves and opened a path for their younger sisters.

Mary Lyon

Mary was the sixth of eight children, born February 28, 1797, on a 100-acre farm near Buckland, Massachusetts to Aaron and Jemina (Shepard) Lyon. She was only five when her Revolutionary war veteran father died. After Mary turned 13 years old, her mother remarried and moved out of the home. Mary, now considered an adult, remained on the farm working for her brother, Aaron, making $1 a week maintaining the household.

At that time, many people believed educating girls was a waste. In most New England towns, the school year was typically ten months long, divided into winter and summer terms. In some places, girls were only allowed to attend summer sessions when boys were needed for farm work. Mary was fortunate that the school in Buckland allowed girls to attend year-round. She left at the age of thirteen but already had more education than most girls.

In 1814, when Mary was just seventeen, she was offered her first teaching job at a summer school in the nearby town of Shelburne Falls. Her teaching experience became the catalyst for Mary to advance her own education, no small task for a nineteenth century woman with little money. Besides this, the emphasis on “lady-like” curriculum at women’s schools was not attractive to her. She wanted a more rigorous program that included the study of Latin and the sciences.

In 1834, Laban Wheaton, a local politician, and his daughter-in-law, Eliza, called upon Mary for assistance in establishing the Wheaton Female Seminary in Norton, Massachusetts. For the Seminary, Mary created the first American curriculum with the goal to be equal in quality to men’s colleges.

It was renamed Wheaton College and just celebrated its 189th commencement.

1835 witnessed Mary developing Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. She wanted to create a rigorous college that made it possible for women who were not wealthy to attend. The yearly tuition was set at $60 and to control costs, required students to perform domestic tasks; Emily Dickinson, who attended the Seminary in 1847, was tasked with cleaning knives.

Mount Holyoke Female Seminary opened in 1837 with 80 girls, with an unheard of curriculum. She required seven courses in the sciences and mathematics for graduation and introduced women to performing laboratory experiments. Field trips were organized where students collected rocks, plants, specimens for lab work and inspected geological formations.

After 12 years leading Mount Holyoke, Mary tragically died. She contracted erysipelas, possibly from a student, and passed March 5, 1849. However the foundation of her school was sound and in 2024 Mount Holyoke held its 187th commencement.

Mary’s very deep religious beliefs, born a Baptist converting to Congregationalism, drove her hard work. Her grave on Holyoke campus bears Mary Lyons’ famous declaration: “There is nothing in the universe that I fear, but that I shall not know all my duty, or shall fail to do it.”

Catharine Beecher

Catharine, the eldest of nine children, was born to Lyman Beecher and his wife Roxana on September 6, 1800. In the home of this famous Presbyterian minister and evangelist, ideas about literature, religion, and reform were constantly under discussion. When nine years old, the family moved to Litchfield, Connecticut, where she attended Litchfield Female Academy. This was the only formal education she ever received.

By the time Catharine was 22 years old, she was engaged to Yale University professor Alexander Fisher. After he died in a shipwreck, Beecher never married and dedicated the rest of her life to education.

In 1823, Catharine founded the Hartford Female Seminary offering a full range of subjects instead of just fine arts and languages. She was an early pioneer of physical education for girls, defying the prevailing notions of women’s fragility and introduced calisthenics to improve women’s health. Unlike other women’s schools, Catherine’s seminary taught women to use their own judgment and become socially useful.

Her younger sister, Harriet, attended the school and also taught at it.

In 1831, the Beecher family moved west when Lyman became president of Lane Theological Seminary, a progressive Cincinnati institution on the Ohio frontier. There, Catharine opened the Western Female Institute, one of several educational institutions where she prepared women teachers in the American West. Harriet also worked at the institute.

In 1836, Harriet met and married Calvin Ellis Stowe, a clergyman and seminary professor, who encouraged her literary activity and was himself an eminent biblical scholar. Like her sister Catharine, Harriet strongly opposed slavery and eventually wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Catherine was also a writer and philosopher. Her essay on “Slavery and Abolitionism with Reference to the Duty of American Females” was published in 1837. It provided a peek into her conservative outlook, often isolating her from the major developments in the history of American reform. She held that all Christian women were abolitionists by definition but urged gradual rather than immediate emancipation. Meekness and tact were necessary in any criticism of slaveholders.

These same conservative views caused her to oppose voting by women.

After Catharine’s financially-troubled Cincinnati school closed, she worked on McGuffey Readers and spent the next decade touring the American West, setting up several female teaching academies. In 1841, she published A Treatise on Domestic Economy, followed by The Duty of American Women to Their Country (1845) and The Domestic Receipt Book (1846). She remained a genteel critic of slavery and foe of the franchise for women, believing that women’s true role as redeemers rested in domestic duties as mothers and wives.

Catharine Beecher died May 12, 1878 in Elmira, New York.

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody

This absolutely amazing woman, Elisabeth Palmer Peabody, was born in Billerica, Massachusetts on May 16, 1804. Her father, Nathaniel Peabody, was a dentist and her mother, Elizabeth Palmer, had a philosophy of life rooted in Unitarianism. Mrs. Peabody home-schooled her children and started her own small school where at age 16, Elizabeth began teaching. Her father taught her Latin and she went on to be a gifted linguist, familiar with more than ten languages.

There were five Peabody siblings, her brothers Nathaniel and George plus sisters, Sophia Amelia and Mary Tyler. Sophia married novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne while Mary married famed-education reformer, Horace Mann.

One of Elizabeth’s early mentors was Dr. William Ellery Channing, the “father of Unitarianism.” She claimed to be raised in the “bosom of Unitarianism.” She also was a member of the Transcendentalist community.

From 1834-1835 she worked with Bronson Alcott at his famous experimental Temple School in Boston. The school was forced to close when Alcott was accused of teaching sex education. Other Transcendentalist-inspired ideals used at the school were also strongly criticized. However their Socratic method of instruction is still popular today.

Elizabeth became America’s first female publisher and her book store, simply known as “13 West Street,” was a center for philosophical discussion. Both Ralph Waldo Emerson and Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. gave lectures there and her publishing venture produced not only Channing’s Emancipation in 1840 but several of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s books. In 1849, she was first to publish Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience.

She opened the first publicly supported kindergarten in 1860 and wanted this Boston school “to awaken the feelings of harmony, beauty and conscience” in students. Doubts about the school’s effectiveness caused her to travel to Germany and observe the model practiced by disciples of kindergarten founder, Friedrich Froebel. Upon returning, she traveled across the country giving lectures and holding training classes. From 1873 to 1875 she published the Kindergarten Messenger.

In addition to her teaching, Elizabeth wrote grammar and history texts, touring America to promote the study of history. In 1865, she wrote the Chronological History of the United States.

Elizabeth championed the rights of Native Americans and edited Sarah Winnemucca’s autobiography, Life Among the Paiutes.

Elizabeth Peabody died on January 3, 1894, in Jamaica Plain and was buried at Concord’s Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. Abolitionist minister Theodore Parker praised her as “a woman of most astonishing powers … many-sidedness and largeness of soul … rare qualities of head and heart … A good analyst of character, a free spirit, kind, generous, noble.”

Three Remarkable Women!!!

Recent Comments