By Thomas Ultican 4/14/2025

Derek Black’s masterpiece of research, Dangerous Learning, reveals the centuries of struggle for Black Americans to become educated. When I arrived at the Network for Public Education conference April 4, I ran into Professor Black (University of South Carolina Law School) and mentioned to him I almost finished reading his book on the airplane. He absurdly wanted to know how boring I found it. The truth is that this beautifully written book is extremely engaging.

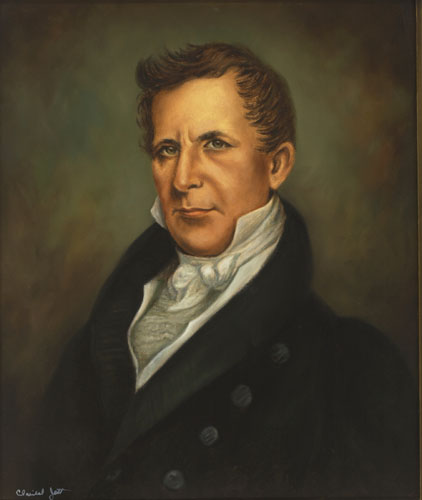

Denmark Vesey

Growing up in Idaho, my knowledge of American slavery is quite lacking. I had never heard of Denmark Vesey, who played a major role in the suppression of education for slaves.

Joseph Vesey was a slave trader who brought 390 enslaved people including Demark to St. Thomas and Saint-Domingue (now known as Haiti) in 1781. Joseph’s slave ship brings the first record of the approximately 14-year-old Denmark. He was sold in Haiti along with the other 390 people but it seems he feigned epilepsy and Joseph was forced to take him back. Soon after, Denmark became Captain Vesey’s trusted assistant.

Black tells this story in about 20 pages in the book. I will cut it down a little.

Denmark learned to read and in 1799 he won the lottery ($1500). He paid Joseph $600 for his freedom and through various means; Denmark became highly educated. He was also inspired by the slave revolution in Haiti. Denmark became an authority on the Bible being known in the community as “a man of the book”. (Page 16) He taught classes at the African Church which became the famous African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church also known as the AME Church. Denmark was obsessed with learning and read widely including classical literature.

In the Old Testament, Vesey found the story of the Israelites’ path from slavery. He taught his friends how the children of Israel were delivered from bondage in Egypt. Professor Black explains:

“In it [the Old Testament], Vesey found a God who stood on the side of the oppressed, not the oppressor, and who intervened in the world not to reinforce slavery but to free the Israelites from it. God consistently assured the Israelites that He would deliver their enemies into their hands if they would follow His will. And following His will did not mean turning the other cheek, fleeing from conflict, or suffering in silence. It often meant smiting those who stood against them, including women and children.” (Page 20)

In 1822, Vesey having been deeply and fundamentally changed by his literacy planned a slave rebellion. He chose July 14th for the liberation of Black people in Charleston. The plan was workable but an enslaved man came forward on May 30th claiming he had been recruited to participate in a slave revolt. After that, Vesey’s plans fell apart and he along with his co-conspirators were put to death. Black noted, “When Frederick Douglass implored crowds of Black men to join the Union Army in 1863, he offered a simple message: ‘Remember Denmark Vesey of Charleston.’” (Page 35)

Unfortunately, it was remembering Denmark Vesey that pushed southerners into an all out suppression of Black literacy that lasted well into the twentieth century.

Suppressing Education

The last open debate on slavery in the South was conducted by the Virginia legislature in 1832. William M. Rivas, a lawyer and member of a wealthy colonial family claimed that elite planters had “held the state’s democratic process in a death grip for decades.” (Page 107) He said they had intentionally limited education not just for slaves but for poor and middle-class White people as well.

While the North was engaged in developing a state supported public education system, the South, under the influence of wealthy elites, absolutely opposed state funding for education.

It was a shock for me to discover that Thomas Jefferson was a white supremacist. In Notes on the State of Virginia he wrote that Black people were “inferior to whites in the endowments of both of body and mind.” (Page 65) He said that this reality posed a powerful obstacle to emancipation.

After the 1832 debate, censorship and anti-literacy in the South took on a life of their own. The South became more and more isolated and intolerant.

For the slaves, seeking literacy was hidden and secretive. Finding the time to study was difficult and a flickering candle could draw attention and suspicion. It is reported that enslaved people would study in caves or in holes they created in the woods.

“In Mississippi, people told of holes large enough to accommodate a group. They called them ‘pit schools.’” (Page 188)

After the Civil War, former slaves were able to openly attend school and the Reconstruction Act of 1867 attempted to force states to pay for it. The Act created three requirements for states to be readmitted to the Union: extend the vote to black men, ratify the 14th Amendment and guarantee a republican form of government. Black noted, “A republican form of government meant, among other things, ensuring public education.” (Page 244)

However the citizens of the south were not going to accept Black people having equal rights. Terrorist groups attacked schools and teachers. The more Union troops were drawn down, the greater the violence became.

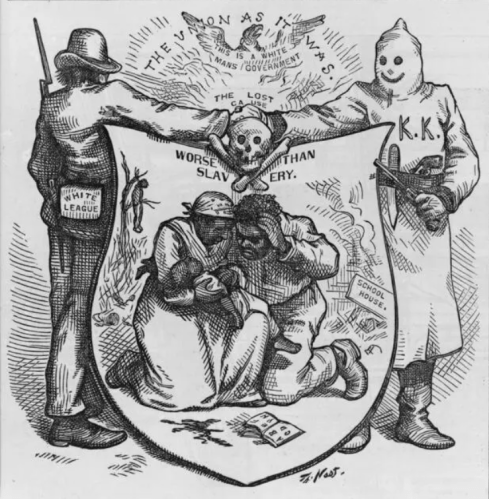

1874 Harper’s Political Cartoon by Thomas Nast

During Reconstruction, 631 attacks on black schools have been documented. White citizens of Tennessee under the leadership of the KKK destroyed 76 Black schools. (Page 261)

In order to secure victory in the 1877 Presidential race, Rutherford B. Hayes agreed to a compromise between southern Democrats and pro-business Republicans to end Reconstruction. Soon after, southern states started rewriting the required constitutions they needed to rejoin the Union. There was a two pronged agenda: “disenfranchise Black voters, and segregate and underfund Black education.” (Page 168) Jim Crow laws became enshrined in the new southern state constitutions.

In 1896, the Plessy v. Ferguson case held up the bogus concept of separate but equal facilities. That same year saw a new Louisiana law that took Black male voter registration from 95.6% of the population to 1.1% by 1904. In 1902, Nicolas Bauer, a man that would become superintendent of public schools in New Orleans, wrote:

“I realize from my limited observation that to teach the negro (sic) is a different problem. His natural ability is of a low character and it is possible to bring him to a certain level beyond which it is impossible to carry him. That point is reached in the fifth grade of our schools.”

The lack of justice and abundance of ignorance is what the Supreme Court tried to rectify with Brown v. Board of Education.

The fact is these two centuries of hostility toward educating all American citizens is still causing harm. Derek Black’s Dangerous Learning is a must read for anyone that cares about justice.

Recent Comments